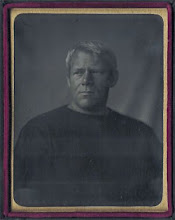

Big Bill Tilden

Big Bill TildenIn honour of the 2009 US Open, here's a tip of the cap and a wave of the racquet to Bill Tilden, a native Philadelphian, and one of the greatest tennis champions of all time.

Photographer Marco Queral shakes hands with a Humpback Whale

Photographer Marco Queral shakes hands with a Humpback Whale On 20 July 1969, Mission Commander Neil Armstrong & Lunar Module Pilot Buzz Aldrin became the first men to walk on the moon. As the lunar module touched down on the moon, Aldrin declared "Houston, Tranquility Base, here. The Eagle has landed." At 10:56 pm Armstrong began his descent to the moon's surface. He stepped off the Eagle and onto the moon, the first human ever to walk on another planet. His words still resonate today: "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind." The event was broadcast back to Earth; at least 600 million people watched live, as Armstrong & Aldrin walked on the moon. Walter Cronkite, who passed away 2 days ago, anchored the CBS news desk and exclaimed "Oh boy!"

On 20 July 1969, Mission Commander Neil Armstrong & Lunar Module Pilot Buzz Aldrin became the first men to walk on the moon. As the lunar module touched down on the moon, Aldrin declared "Houston, Tranquility Base, here. The Eagle has landed." At 10:56 pm Armstrong began his descent to the moon's surface. He stepped off the Eagle and onto the moon, the first human ever to walk on another planet. His words still resonate today: "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind." The event was broadcast back to Earth; at least 600 million people watched live, as Armstrong & Aldrin walked on the moon. Walter Cronkite, who passed away 2 days ago, anchored the CBS news desk and exclaimed "Oh boy!" Canadian Pianist Glenn Gould Playing Concert Grand Piano as He Records Bach's Goldberg Variations in Recording Studio

Canadian Pianist Glenn Gould Playing Concert Grand Piano as He Records Bach's Goldberg Variations in Recording Studio From Lux et Nox

From Lux et NoxWilliam Claxton called photography "jazz for the eyes". But jazz photographs have to be music to the ears as well. The best pictures of musicians are drenched in the sound of their subjects. Claxton's photographs…are imbued with the subjects' music style and personality. As Bill Evans hunches over the keyboard there is so little to be seen - ear, hair, neck, a glimpse of spectacles - that he shouldn't be recognisable but, like the lightest touch of his fingers on the keys, these few details are enough to identify him immediately and reveal the admonition at the heart of his technique: it takes more strength to caress the keys that to pound them.

Because he was a true improviser, Claxton's photographs look lucky and inevitable in equal measure. In a famous picture of Kenny Dorham soloing, a plane passes overhead like a note of music floating clear of the trumpet. Although they are frequently seen performing on small, cramped stages, Claxton's people are rarely crowded by the picture frame.

Continuing the musical parallels, it's tempting to characterise this light, spacious style as west coast. Claxton grew up in southern California and is probably best known for his portraits of LA-based musicians such as Art Pepper and Chet Baker. The off-the-cuff glamour that marks Claxton's pictures of Pepper and Baker served him even better when he was photographing celebrities. The trademark suggestion of a spontaneously improvised pose is like the equivalent, in a still image, of Steve McQueen's impassive idea of what constituted acting and action: doing nothing and making the idea of more look histrionic.

Claxton in a nutshell: everyday greatness and a charged sense of the ordinary in the same instant.

- Geoff Dyer, "Jazz For The Eyes", The Manchester Guardian, Wednesday 15 October 2008

They were a particularly ambivalent yet strangely fitting pair of friends. Francis Bacon was one of the pre-eminent post-modernist painters of our times, while John Deakin, despite a prolific career as a photographer for British VOGUE, remains a relative unknown. Now, an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York provides an opportunity to reassess Deakin's work, in the process shedding significant light on the influence and inspiration photography had on Bacon's painting.

A self-taught painter, with no real formal art education, Bacon made conflicting claims about his use of photographs. In a conversation with Michel Archimbaud which took place in 1991, he said that "Photographs are only of interest to me as records. I know people think I've often used it [photography], but that isn't true. But when I say that to me photographs are merely records, I mean that I don't use them at all as a model. A photograph, basically, is a means of illustrating something and illustration doesn't interest me." However, in the same discussion, Bacon explained that "Since the invention of photography, painting really has changed completely. We no longer have the same reasons for painting as before. The problem is that each generation has to find its own way of working. You see here in my studio, there are these photographs scattered about the floor, all damaged. I've used them to paint portraits of friends, and then kept them. It's easier for me to work from these records than from the people themselves, that way I can work alone and feel much freer. When I work, I don't want to see anyone, not even models. These photographs were my aide-memoire, they helped me to convey certain features, certain details."

Bacon's disengenuity at this stage in his life (he died a year later, in 1992), seems designed to contradict earlier statements made in a noteworthy series of interviews with his friend, the art historian David Sylvester. In those discussions, which began in 1962 and continued through 1974, Bacon spoke much more specifically about his use of photography. "The thing of doing series may possibly have come from looking at those books of Muybridge with the stages of movement shown in separate photographs. I've also always had a book of photographs that's influenced me very much called POSITIONING IN RADIOGRAPHY, with a lot of photographs showing the positioning of the body for the X-ray photographs to be taken, and also of the X-rays themselves." Later, referring to photographs by Marius Maxwell which he admired in the 1924 publication, STALKING BIG GAME WITH A CAMERA IN EQUATORIAL AFRICA, Bacon acknowledges that "one image can be deeply suggestive in relation to another. I had the idea that ...textures should be very much thicker, and therefore the texture of, for instance, a rhinoceros skin would help me to think about the texture of human skin." In addition, Bacon was well aware of DOCUMENTS, one of the great European magazines of the late 1920's and early '30's; one issue in particular featured photographs of slaughterhouses, which became a recurring motif in several of his paintings.

He also alludes to different, more oblique role photography had on his approach to looking at things. "Photographs are not only points of reference; they're often triggers of ideas...I think one's sense of appearance is assaulted all the time by photography. So that, when one looks at something, one's not only looking at it directly, but also looking at it through the assault that has already been made on one by photography. I've always been haunted by them [photographs]; I think it's the slight remove from fact, which returns me onto the fact more violently." From these comments, it becomes clear that Bacon was discussing not just with the influence specific images had on his work, but also the inspiration he derived from the particular regard of photography.

Even when creating works that referred to other paintings, Bacon preferred to work from photographs. The Velazquez and Bacon exhibition at the National Gallery imparts a sense of reunion that is misleading. Bacon's four studies from Velazquez' portrait of Pope Innocent X all derive from photographs and reproductions of the earlier masterpiece rather than any first- hand experience with the actual painting. Despite traveling to Rome, Bacon never saw the "Innocent X" in the Doria-Pamphilj Collection. He spoke, instead, of "a fear of seeing the reality of the Velazquez after my tampering with it." Andrew Sinclair suggests that Bacon's use of photography in this regard derives from a Surrealist approach to picture-making, in which the artist finds inspiration in the objet-trouve, the random thing or postcard or photograph.

Interestingly, Bacon rarely refers specifically to his use of Deakin's portraits. Deakin started photographing in 1939 and continued to work intently if intermittently through the mid-1960's. His heyday occurred during the '50's when he was under contract to VOGUE (where he had the dubious distinction of being the only staff photographer ever fired twice by the same administration). Although his tenure there was short-lived, in a period of approximately 4 years he produced more work than his contemporaries at VOGUE, including Norman Parkinson, Clifford Coffin and Cecil Beaton. Deakin photographed everything for VOGUE, including fashion and beauty, but his forte was portraiture. The poet and novelist, Elizabeth Smart, remarked that Deakin had "tyrannical eyes," and the art critic, John Russell, wrote that Deakin "rivaled Bacon in his ability to make a likeness in which truth came unwrapped and unpackaged. His portraits, like Bacon's, had a dead-centered, unrhetorical quality. A complete human being was set before us, without additives." Deakin's portraits were characterised by a monochromatic austerity and raw clarity that wasn't in keeping with the buoyancy of the work done by Parkinson or Beaton; indeed, it precedes the nearest thing to it - the photographs of David Bailey and Richard Avedon - by a decade. "Whoever the sitter, Hollywood actor, celebrated writer or valued friend," writes Robin Muir in his catalogue essay, "Deakin made no concessions to vanity, his portraits are never idealised or evasive, and typically contain no pretense to flattery. There is no soft focus, no blurring or retouching. At their most extreme these images are cruel depictions. And even now, over forty years later, his prints are still defiantly modern."

Despite creating a memorable body of work, Deakin remains largely forgotten. His prints were outsized and consequently not easily archived. Deakin himself distrusted their worth. "He really was a member of photography's unhappiest minority whose members, while doubting its status as art, sometimes prove better than anyone else that there is no doubt about it," recalls his friend, Bruce Bernard. His greatest undoing, though, is evident in his portraits. Many of his subjects were his friends and drinking companions from the pubs and clubs of Soho; Bacon and Deakin, along with Michael Andrews, Frank Auerbach, and Lucien Freud comprised a group (virtually a subset of R.B. Kitaj's "School of London"), that would frequently gather for drinks at Muriel Belcher's club, the Colony Room, a setting described as "a place you could take your grandmother, and possibly your father, but not your mother." But while Bacon would regularly return to his studio from a late night out and religiously put in several hours painting, drinking affected Deakin's work and led to his dismissal from Conde Nast. His career as an independent photographer was not a success and his life devolved into a series of trips abroad.

Deakin's portraits did have a life, albeit largely unacknowledged, in Bacon's paintings. Bacon commissioned many of Deakin's portraits as reference points for his own work. "Even in the case of friends who will come and pose," Bacon said, "I've had photographs taken for portraits because I very much prefer working from the photographs than from them. I think that, if I have the presence of the image there, I am not able to drift so freely as I am able to through the photographic image. This may just be my own neurotic sense but I find it less inhibiting to work from them through memory and the photographs than actually having them seated there before me. I don't want to practise before them the injury that I do to them in my work."

Bacon's studio was notoriously chaotic and cluttered. "My photographs are very damaged by people walking over them and crumpling them and everything else, and this does add other implications to an image," he stated. To see the exhibition of Deakin prints from Bacon's estate consequently becomes an experience in watching the figure deconstruct according to the state of destruction in which the print has settled, much as the figures in Bacon's painting appear tortured, convoluted and deconstructed. While Bacon spoke about the ways in which he used photography, he rarely specifically cited Deakin's photography by name. Nor did he comment on the inspiration he drew from these torn and crumpled prints. However, in the same manner in which photographs of Velazquez' portrait of Innocent X had an object quality and presence for Bacon above and beyond that of the work itself, it is not inconceivable that Deakin's photographs, transformed by the damage sustained while in his studio, came to represent much more than simple aide-memoire for him.

In a different context, Bacon once commented that "his [Deakin's] work is so little known when one thinks of all the well-known and famous names in photography - his portraits to me are the best since Nadar and Julia Margaret Cameron." Deakin's photographic output essentially ended in 1961, yet he and Bacon retained some semblance of a friendship. It was Bacon who was listed as Deakin's next of kin during his last hospital stay and it was Bacon who paid for his convalescence in Brighton where Deakin died of heart failure in 1972. But the kinship seems strongest in the work. The prints of Deakin's photographs which Bacon held in his studio, set alongside Bacon's painted portraits, are evidence of the influence and inspiration photography provided for Bacon. Deakin could have been speaking for Bacon as well when he said "Being fatally drawn to the human race, what I want to do when I photograph it is to make a revelation about it. So my sitters turn into my victims."

- Peter Hay Halpert, "Influence and Inspiration: Francis Bacon's Use of Photography," originally published in Aperture, Fall 1996 & updated here 2009